Building with patience

Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast.

As a software engineering manager I have had the privilege to meet many software developers who have applied to our company over the past few years. I enjoy interviews, most of the time, because they’re an opportunity to get to know people and geek out together about product development, innovation, web app development, software architecture, user experience design, and other exciting topics.

Last year, I had a certain interview experience that left a lasting mark on me. A resume came by me that seemed amazing—a candidate who had graduated from a top school, interned at Google, and then spent 10 years at Facebook, promoted over time from junior to intermediate to senior developer.

The beginning of the interview went well. The candidate was well-spoken, and he outlined his past experience well. He seemed intelligent and articulate. But then I started asking for details.

Me: “You say you used an OCaml version of React at Facebook with a JS interop instead of plain JS. That’s really interesting! What are the pros/cons in comparison to plain ReactJS?”

Candidate: “Oh, I’ve never tried React outside of Facebook.”

Me: “You mentioned you have used OOP for backend development—what design patterns do you rely on?”

Candidate: “What do you mean by design patterns exactly?”

Me: “What are some differences between monolithic and microservices architectures?”

Candidate: “… I’m sorry I’m not familiar with that.”

As I asked these questions and others I started to see in this candidate’s eyes and expressions a sort of shock that I can still feel now—it looked as if he was saying “this is a question I could be expected to know?”

What struck me is that this candidate was clearly smart. He had potential, but he spent 10 years at Facebook in a bubble. And he did not know he was in a bubble.

Accidental Complacency

In my last article, Building with urgency, I wrote about why we ought to live with vigilance and be cautious of wasting potential. Certainly, we should use each moment wisely, and yet, “not all those who wander are lost.” A subtle corollary to the principle of urgency is that we must also fear the consequences of missed serendipity, and in so doing avoid an accidental complacency that results from ignorance.

Perhaps the reason this interview sticks in my memory so profoundly is that it made me fear that I myself must be living oblivious to important knowledge and important opportunities that I ignore without knowing I ignore them. It made me reflect that we all live with some blindness to things and have fallen into beliefs, habits, and assumptions that we by definition cannot see that we’ve fallen into.

This experience was a powerful reminder for me to get out of my comfort zone, and not just that but to stop working sometimes and make more space for the unexpected. We need to get outside ourselves, have weekends, coffee chats, go to conferences, read new books, talk to friends and strangers, and say yes to invitations that seem unnecessary to accept.

And it’s not just avoiding complacency. Life-changing opportunities regularly come from unplanned encounters. That’s what happened in the story of the creation of the iPod. Tony Fadell, the lead behind the iPod project, didn’t get the gig at Apple by applying. He was building his startup Fuse, trying to build a digital audio jukebox for listening to music on your TV, but suddenly the internet bubble burst and things were not looking good for him.

One day at the peak of my desperate, scrabbling attempt to fund my company, I had lunch with an old friend from General Magic. I told him what I was working on and what I was struggling with—the swirling, nauseating mix of excitement about what we were creating and the sinking horror that I’d have to shut it all down. He commiserated, ate his sandwich, and wished me well.

The following afternoon he had lunch with a colleague who worked at Apple. They mentioned they were kicking off a new project. Did he happen to know anyone with experience building handheld devices?

I got a call from Apple the next day.

- Tony Fadell, Build

Fadell went on to pitch the idea of the iPod to Steve Jobs a couple months after joining the team, and seven months later it was completed and released to the market. The iPod’s success marked a major turnaround for Apple, ultimately saving the company from stagnation. At the time, Apple was only a $4 billion company (for comparison, Microsoft was $250 billion at the time!). Fadell’s work at Apple, in building the iPod and then leading the development of the iPhone, contributed to hundreds of billions of dollars of value, all of which only could come to fruition because he spent time, in his moment of peak desperation, to get lunch with an old friend.

The best builders are patient

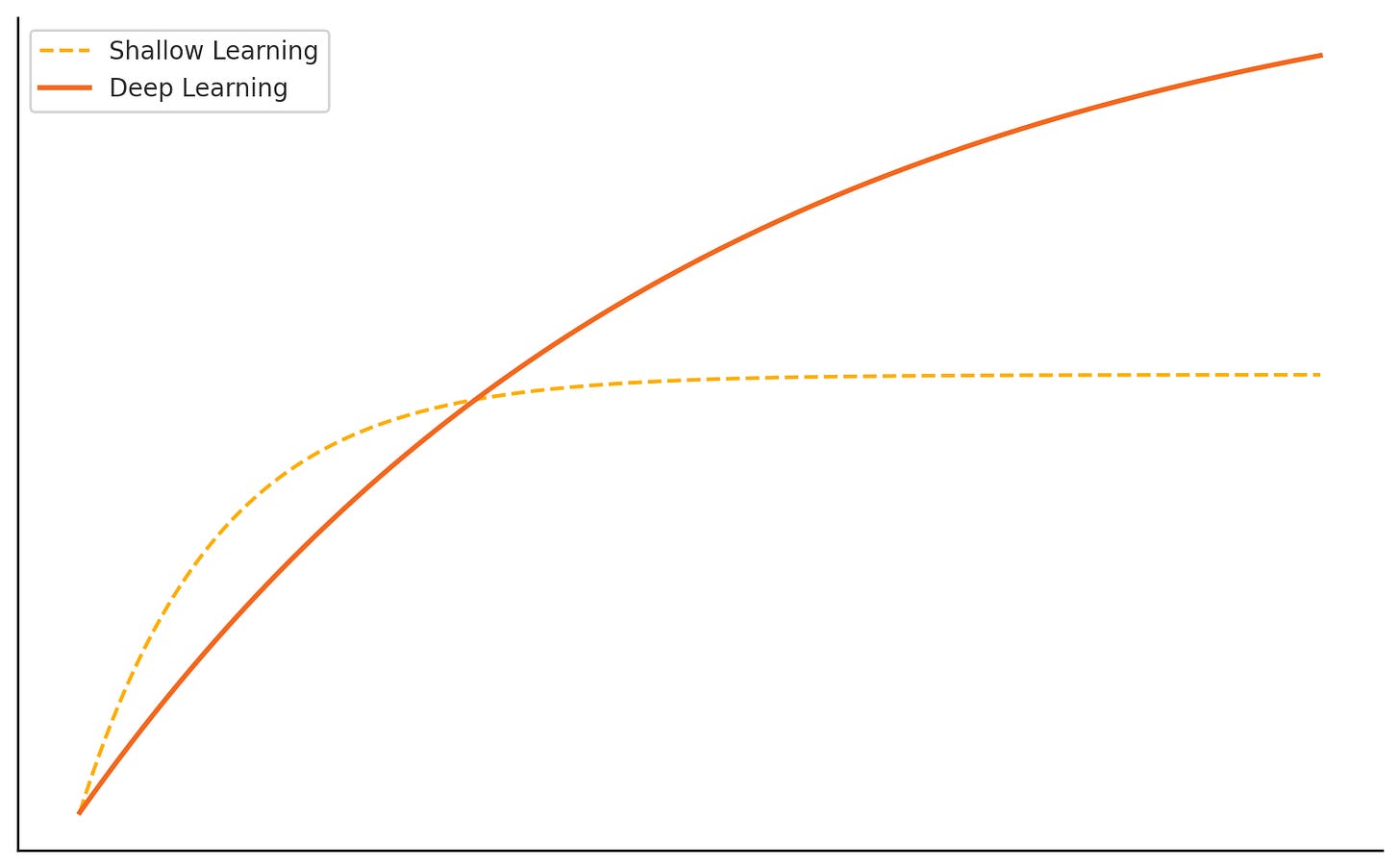

The best engineers I’ve seen are fast. And they’re fast because they have built a strong first-principles knowledge. And they built this by being slow.

Meandering along the way and getting distracted from the task at hand can pay off well in the long run. Great builders aren’t satisfied with ambiguity in their understanding or mental models that don’t quite line up with reality. Even if it takes a few hours extra to dig into obscure documentation or navigate the source code of a framework you’re using, a good developer does it anyway, building over the course of years a refined understanding and knowledge base that makes people wonder “why do you even know that?”

This is why in hiring the primary trait I look for is curiosity. Those who love to learn and experiment, not even with a purpose, but for the sake of enjoyment and discovery, become stronger and tend to enjoy coaching others, setting the stage for long-term excellence.

Curiosity can go wild, of course. There are times when learning is incredibly relevant, but excessive discovery can be just as problematic as living in ignorance, as Seneca described well in the first century:

The primary indication, to my thinking, of a well-ordered mind is a man’s ability to remain in one place and linger in his own company. Be careful, lest this reading of many authors and books of every sort may tend to make you discursive and unsteady. You must linger among a limited number of master-thinkers, and digest their works, if you would derive ideas which shall win firm hold in your mind. Everywhere means nowhere. When a person spends all his time in foreign travel, he ends by having many acquaintances, but no friends. And the same thing must hold true of men who seek intimate acquaintance with no single author, but visit them all in a hasty and hurried manner. Food does no good and is not assimilated into the body if it leaves the stomach as soon as it is eaten; nothing hinders a cure so much as frequent change of medicine; no wound will heal when one salve is tried after another; a plant which is often moved can never grow strong. There is nothing so efficacious that it can be helpful while it is being shifted about. And in reading of many books is distraction.

…

Each day acquire something that will fortify you against poverty, against death, indeed against other misfortunes as well; and after you have run over many thoughts, select one to be thoroughly digested that day. This is my own custom; from the many things which I have read, I claim some one part for myself.

- Seneca, IV, Loeb Classical Library Edition

While accidental complacency can result from a closedness to fortuity, excessive openness to discovery will result in confusion, and a lack of depth.

It reminds me of Steve Jobs’ criticism of consultants. While consultants go from project to project, company to company, and build a wide breadth of experiences—they never own the results of their actions over the long-term, and lose a great deal of learning as a result.

I think that without owning something, over an extended period of time—like a few years—where one has a chance to take responsibility for one’s recommendations, where one has to see one’s recommendations through all action stages and accumulate scar tissue for the mistakes and pick oneself up off the ground and dust oneself off, one learns a fractions of what one can.

Coming in and making recommendations and not owning the results, not owning the implementation, I think is a fraction of the value, and a fraction of the opportunity to learn and get better…. You do get a broad cut at companies, but it is very thin. It is like a picture of a… banana! You might get a very accurate picture, but it is only two dimensional; and without the experience of actually doing it, you never get three dimensional.

So, you might have a lot of pictures on your walls. You can show it off to your friends… You can say, look! I have worked in bananas, I have worked in peaches, I have worked in grapes. But you never really tasted it.

- Steve Jobs, speaking to a group of MIT business school students (full video)

Compounding knowledge cannot be acquired by erratically jumping from topic to topic. Often, especially from junior engineers, I see resumes filled with technologies and programming languages. Knowing 100 programming languages as an engineer is not necessarily impressive, but it would be impressive to see an engineer who could describe in detail the tradeoffs they see between three languages (for example, building with a strict functional language like Haskell versus using a lower-level typed language like Rust versus building domain-driven architectures with C#/Java). Both examples of engineers are curious and experimenting with new things, but the latter is able to learn with perspicacity, seeing principles that are only perceptible when building with patience, dwelling in the new, ruminating over it, and contemplating its power and its limits.

Consequentialist and deontological thinking

The pattern of difference between hurried doers and patient learners also reminds me of an apparent dichotomy taught in moral philosophy, the endless debate between consequentialist and deontological morality.

Consequentialism holds that the morality of actions are determined by their consequences. If the outcome is good, then the action is moral.

Deontological morality, on the other hand, focuses on the inherent morality of the actions themselves. It generally holds that there is an objective moral order, and acting within the pattern of behaviour that aligns with this order is primary.

But there’s a funny interplay between these two. If one considers longer and longer time scales, with more and more impacted parties, then his consequentialist thinking increasingly aligns with the order of morality argued for by the deontologists.

The good negotiator doesn’t focus on his own wants; he focuses on the other’s needs and adapts his asks accordingly. An even better negotiator understands that his dealings with the counterparty may continue in future negotiations, and so is just and reasonable in his dealings with him, sacrificing short-term gains. And the wisest negotiator understands that he doesn’t even know how goodwill may fortuitously come back to help him in the future, and so he sees the negotiation no longer as adversarial, but purely a collaborative problem-solving activity with a partner.

As we deepen our consequentialist wisdom, and we extend to act in ways that pay us back in ways we know we ourselves could not predict, all of a sudden the consequentialist and the deontologist converge to the same perspective.

Like this, the one who builds with urgency and the one who builds with patience also converge to the same perspective. By opening ourselves to new knowledge, with patience, and in reasonable servings, we live in the virtuous path that maximizes forward movement, by giving space for novelty and slowness, every now and then.

“Dress me slowly, I'm in a hurry.”

- Napoleon Bonaparte

While I have little to offer, myself, in terms of experience-based advice re success in the field of software development, I can definitely appreciate advice based on Tolkien, Seneca, Jobs, and the practical convergence of two different approaches to the philosophy of morals! Further, this lines up nicely with one of my favourite X posts from Dave Plummer, creator of Windows Task Manager: https://x.com/davepl1968/status/1777846782904696921

The path to (universal) knowledge is through the deepening of the particular in a faithful and intimate relationship. This goes contrary to the zeitgeist, which tends to reduce knowledge to accumulating information and facts.